Between the Bottomlands and the World is a video trilogy and book project that explores a rural mid-western town of 6000 people—a place of global exchange and international mobility, inscribed by post-NAFTA realities. Recent scholarship shows that immigrants are moving to rural communities in the Midwest at the same rate that they are moving to cities. Historically, Midwestern cities were home to industries that attracted immigrant workers, becoming hubs for those seeking work. Today, many remaining industries lie outside the city, in rural towns unencumbered by urban regulations. In the case of Beardstown, the major industry—a slaughterhouse—recruited new immigrants from the Texas border, Mexico, and later from Congo, Togo, Senegal, Puerto Rico and other Caribbean locales, to what was an all-white, “sundown” town.

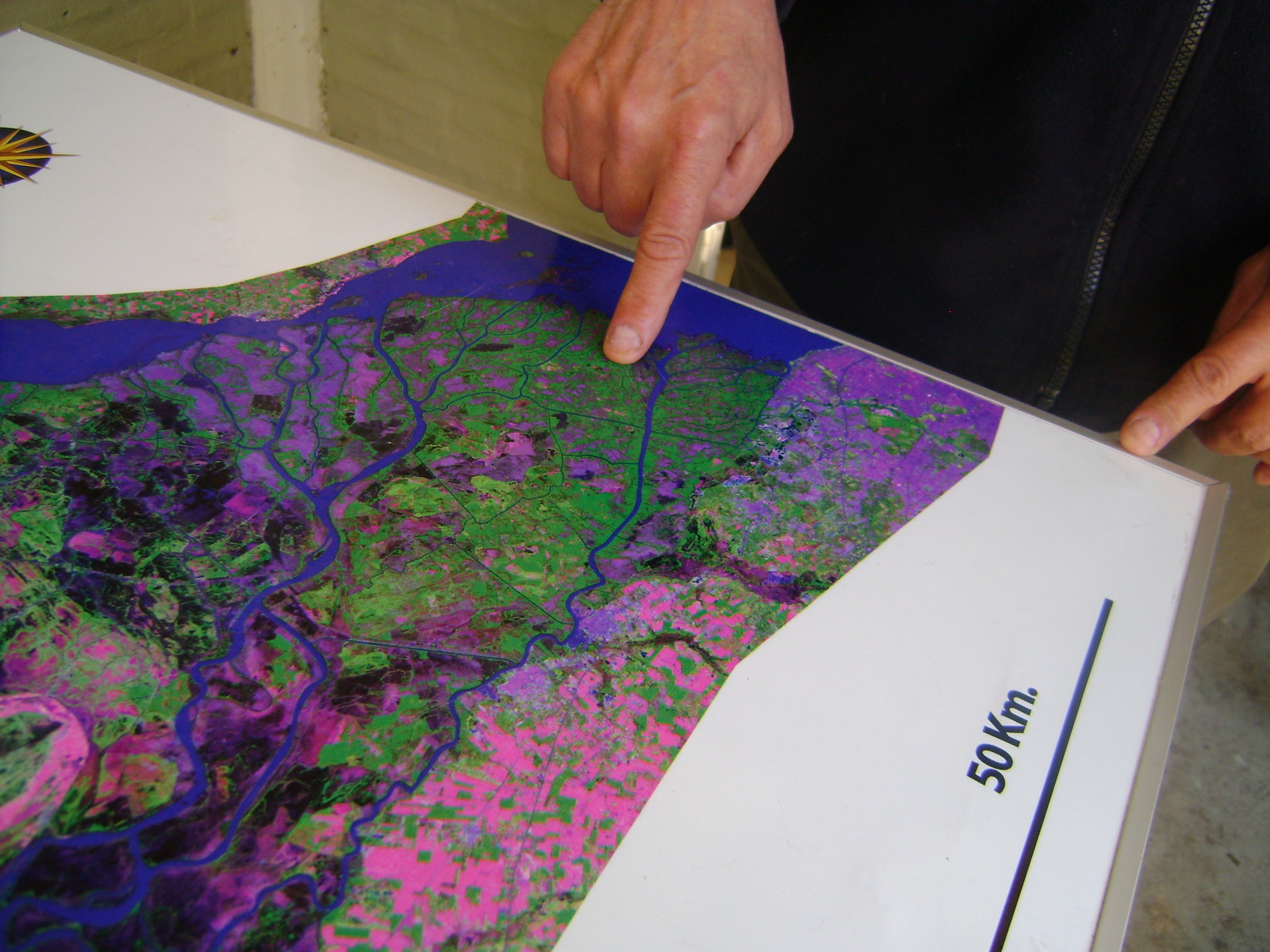

As social struggles have been fought and won in this small town, its existence has consistently relied on one multinational corporate giant, which is currently Cargill. Hence, workers come and go, hogs are slaughtered and shipped out at the rate of 18,000 a day, grain travels from the fields to the Cargill loading docks on the Illinois River where they enter national and international markets. Between the Bottomlands… tells this story of global mobility in a rural, Heartland town, through looking at the trades of meat and grain as well as the stories of newcomers. One chapter (Submerging Land) looks at the engineering of contemporary agricultural land from a network of rivers and marshes that once surrounded the town, while a second (Granular Space)explores the vast transportation network connecting Beardstown to ports across the globe. A final, forthcoming, video (Moving Flesh) uses interviews with long-time residents and new-comers, from such disparate locales as Detroit, Mexico and Togo, and re-stages them through fictionalized and composite characters, relating the current effects of globalization on individuals and communities. This final video is subtitled in French and Spanish.

The first two videos are included in their entirety below, along a short introduction to Moving Flesh.

A book will accompany the videos, with an experimental glossary and an essay by Faranak Miraftab, an urban planner and principle researcher on this project. Between the Bottomlands and the World is a project by Ryan Griffis and Sarah Ross.