Sarah Augusta Lewison and Dan S. Wang

“What time is it on the clock of the world?”

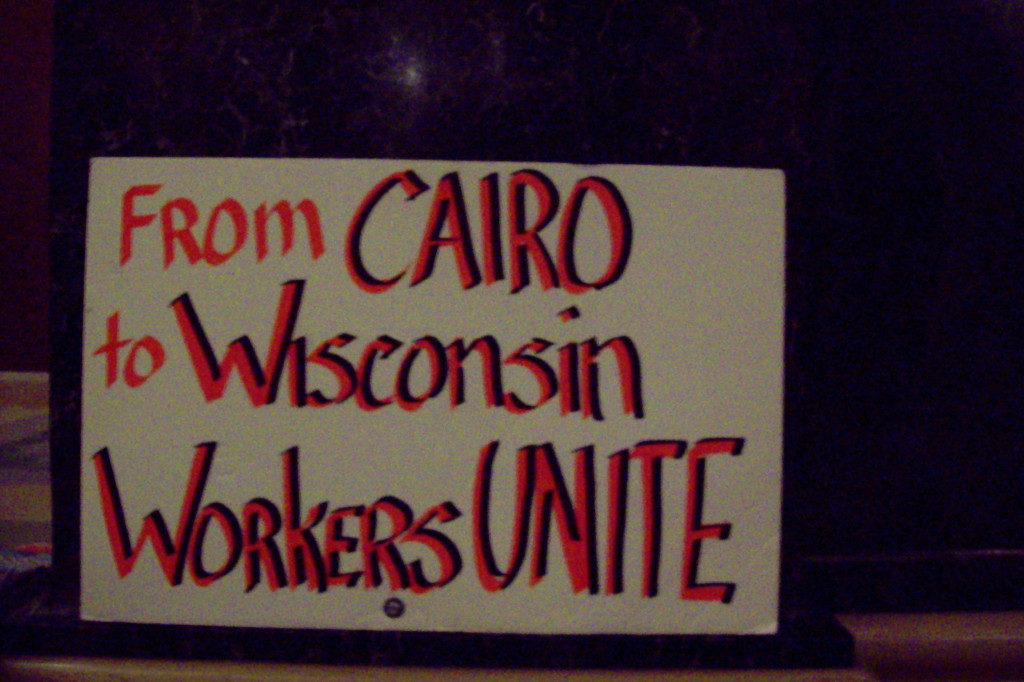

This treatise and travelogue follows on an impulse to revisit the outbreak of popular protest in Madison, Wisconsin in February of 2011, when a mass movement was born, one that linked at a key moment to protests in Tahrir Square and prefigured the months-later Occupy Wall Street in New York. When a reactionary state governor threatened labor autonomy, thousands of Wisconsin workers, students, pensioners, and families occupied the state capitol building for sixteen days and nights, and later forced an early election. Encouragement came from supporters all over the country and the world. An Egyptian protester in Tahrir Square acknowledged the Wisconsin workers’ struggle through signs delivered virally; Wisconsin protest singers paid the favor forward by posting video tributes to those in the heat of Spain’s Indignados movement. The horizontal contagion of uprisings across different national and regional contexts in 2011 revealed a sympathetic political imaginary of resistance that could instantly bridge great distances.

But as the uprisings, occupations, and mass movements projected themselves and were received as spectacularized images, their translocal and transcontextual significance was diluted; either flattened into broad universals about human struggle, or overshadowed by local urgencies. As demonstrations met with repression, the euphoric exchange of transnational support was preempted by the spectacle of heavy policing, leading viewers to experience the unrest as the disciplining of unruly publics. In this essay we look to the rhetorics of recognition between contexts of those connected by but suffering unequally from the predations of neoliberalism in the year 2011. Admitting our own investment in the reciprocal recognition between peoples engaged in different struggles, we mourn that the translocality could not be sustained. But we also understand why. Protest politics based on the mass spectacle model preordains the transnational factor as an easily ignored superficiality.

Bearing in mind that the temporal dimension shapes the evolution of political consciousness and capacities for resistance, we conduct an exploratory mapping of political time (and space) in two locations outside the flash points of political outrage in 2011: the small city of Benton Harbor in the deindustrialized American Midwest, and the villages of Lashihai outside Lijiang City in southwestern China. In exploring how locations with different developmental experiences but convergent futures are raked by neoliberalism, we look for routes of translocal resistance that are linked to communities’ material and symbolic histories. Drawing on Dene scholar Glen Coulthard’s work on recognition politics, we suggest a process for building non-spectacular political translocality that we call mutual self-recognition. We end with a meditation on the realm of symbols as a visual terrain through which a process of mutual self-recognition may begin.

1 . P O L I T I C A L U N E V E N N E S S A N D P O L I T I C A L T I M E

Following Marx, geographer Neil Smith argues that capitalist space contains within it an uneven temporal dimension marked by economic cycles and what he calls the rhythm of accumulation. Smith emphasizes the disruptions brought on by economic crises as setting the stage for new rounds of expansion and accumulation. He stresses the geographical differentiation resulting from crisis, an uneven destruction of value followed by openings for new expansion.1 This mobility of accumulation and production over time and between places produces that contradiction within capitalism known as uneven development. But beyond noting the periodicity of crisis, Smith does not elaborate on temporal unevenness even though this seems to be key for understanding present conditions, as no single economic sectoral crisis can be isolated from any other. With states, sectors, and individual enterprises all experiencing unsustainable levels of debt, declining profits, rising resource costs, and increasing social inequality, all kinds of crises are now intertwined. It is the ubiquity of that narrative–stacked and overlapping sectoral bubbles and business cycles– widespread, interwoven, and contemporaneous, site-specific but common, that produces the present relentlessness of capital seen nearly everywhere.

The strings of anti-systemic protests such as in 2011 revealed a distinction between the political temporalities of popular response, corresponding to the acute crisis and the chronic crisis. On the one hand, there is the compressed time of unrest, the hour-by-hour storylines that bring mass movements into being, telecommunicated across continents. On the other, there is the extended time of the neoliberal creep, especially in places outside densely populated centers of camera-friendly insurrection, places where cultures of resistance and self-preservation evolve over years and even decades. Understanding variable temporalities helps us think through a geography of resistance. Uprisings sprout in response to acute, unmanageable crisis–as in Tunisia, sparked by a rapidly circulating story of gross injustice, and then in Egypt, where images of the unfolding Tunisian revolution combined with a sudden inflation of bread prices to produce uncontrollable pressures. Mass response sets in motion the time of upheaval. By contrast, slow burning crisis–for example, incremental land grabs, piecemeal legalized robbery, episodic erosion of public goods–produce a differently timed resistance, not only less prone to spectacularization but somewhat difficult to capture in images at all.

In “Occupy Time,” Jason Adams argues that Occupy Wall Street moving beyond its investment in occupied space and towards one that extends into time. In other words, the question remains of what strategies would produce a sustained disinvestment in the current institutions, equal to the durational grasp of capital.2 We arm ourselves too with the variabilities of the temporal, understanding that our thoughts exist between past and future, between memory and preparation, in a struggle to grasp time in the project of cultivating political reciprocity and, ultimately, solidarities of real use.

Perhaps the most radical formulation of political temporality comes from James and Grace Lee Boggs, who speak of “the clock of the world,” a notion of political time that overflows the scale of a single generation.3 The Boggs’ use of time as a framework extends the understanding of political effect to the present urgencies of the anthropocene. They call for consideration of present vectors, forces and capacities so that a new vision of society may emerge that brokers accountability between dignified subjects, locally and transnationally.

2 . O N T H E E N D S O F T H E E A R T H :

L A S H I H A I A N D B E N T O N H A R B O R

On the plateau of northwest Yunnan province, Lashihai is a highland lake surrounded by a dozen Naxi villages, a minority ethnic group. Although the Maoist era wrought dramatic change and loss, the region remains remote from the state and the indigenous people retain unique identities that are tied to their long tenure in this place. Until recently, locals practiced traditional subsistence agriculture and commoning in nearby forests. Some families still share labor. The Lashi Valley, surrounded by foothills rising to snow peaks and then down to the first curve of the rushing Yangtze, is one of the most bio-diverse temperate ecosystems in the world. The area’s cultural and ecological diversity led to its designation as a province level nature reserve and a UNESCO Natural World Heritage region. Significantly, Lashi Lake has become the major water source for nearby Lijiang City, a growing tourist destination receiving 4 million visitors yearly. Village farmers are repeatedly compelled to reduce their plots as the lake expands to provide for Lijiang. As their farming incomes drop, they receive cash compensations which they often use to purchase heavy equipment, their entree into the global economy. Recently the state gave farmers trucks as incentives to start businesses.

Historically unassimilated into the Han culture, there are remnants of autonomy in this region. For example, in 2008 when the local Party-nominated chief was discovered skimming land compensation payments, a row erupted and the chief was sent off and not replaced. In a quiet contagion, the other villages around the lake dispatched their chiefs as well. Officially-sanctioned enclosures also have met with resistance, which in some cases were answered with intimidation. When a village closer to Lijiang protested the conversion of their fields into a golf course, two farmers turned up dead; there was compensation but no prosecution. Lashi is at the edge of time, where a new freeway traces one of the earliest sustained projects of global trade, the ancient tea-horse road between Kolkata and Puer, through the provincial capital, Kunming, and on to Vietnam. As farmers begin to follow international prices, they take awful risks with monocropping and soil inputs, hoping to make better sales to the buyers roaming the region in four-ton trucks during harvest times. All this happens while their traditional customs are marketed as one of Lijiang’s main attractions.

Upon arriving we were led to a new construction project in the fields opposite our host’s compound. Family plots are customarily divided into small portions to equalize access to water and different soils. Crops are companion planted in the resulting irregular fields, producing a verdant quilt. But here, the small river flowing from the foothills had been straightened and confined by rock walls. These newly disciplined channels were bordered by stone paved roads that led to uniform rows of identical peach trees, recently planted in the spring mud. Now that the land is fungible, a developer, with the blessing of district level officials, had convinced some villagers that tourists will come to a heaven of peaches beneath the brilliant blue sky, the snow peaks rising above the lake. The walkway stops at the road but heads toward the lake with only our host’s and their neighbor’s land in between. The characters on large bright red signs fronting the embryonic peach orchard exhort the passersby with the larger agenda of penetrating the valley and beyond to further commerce under the guise of development: SPEED CONSTRUCTION OF A NEW SOCIALIST COUNTRYSIDE!. And on the other side of the signs: GRAB THE LAND AND ORGANIZE IT. BUILD A PEACH INDUSTRY.4

*

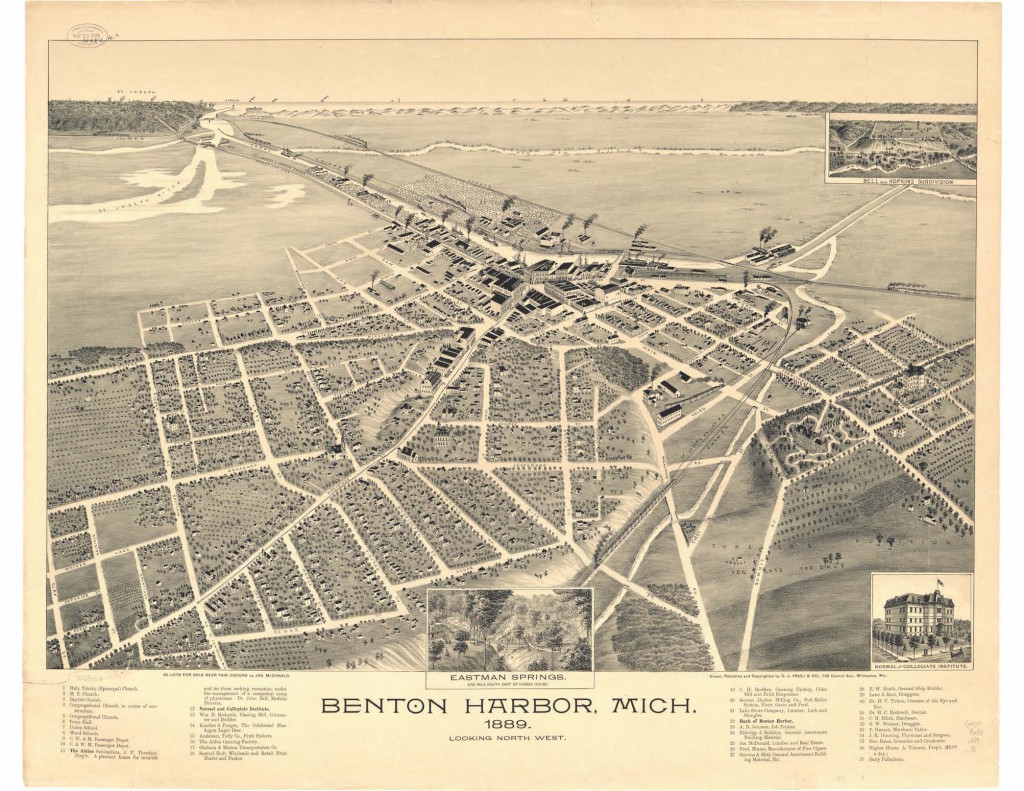

Benton Harbor, today a city of 10,000 on the southeast shore of Lake Michigan, was home to makers of auto parts and consumer goods. An 1889 map shows tree-flecked residential lots and factories with black clouds billowing out of their smokestacks, bordering a ship-lined canal. At the top, ant-like steamers trawl across the lake, which is ornamented at its shore by rows of sandy hills. These dunes loom to 30-plus meters, washed in by the freshwater sea left behind by the last glacier, forming rare sand and wetland ecosystems. In 1917, Benton Harbor newspaperman John Klock bought 90 acres of lakefront dunes and forest, and gave it to the city “in perpetuity” as the Jean Klock Park.5 Standing as a memorial to the Klocks’ deceased young daughter, the forest, beaches, and dunes were open to anyone for picnics, play, baptisms, and solace.

Today new luxury housing punctures the former forest, and holes six through eight of a Jack Nicklaus “Signature” golf course mar the majestic sand hills, the result of 22 acres of the park being taken into private hands despite legal challenges. At around the same time, Benton Harbor’s elected government was replaced by a state-appointed “emergency manager” empowered to sell off public assets and break employee contracts. Benton Harbor’s is the story of many a Rust Belt town: automation, job losses, plant closings, white flight, structural racism, and tax rolls that can barely fund basic services.[i] When jobs were plentiful, blacks moved up to houses with yards and whites fled to the neighboring city of St. Joseph. As the economic shocks of the 1970s advanced, layoffs disproportionately hurt African Americans and the city lost half its population. Remaining residents got stuck with tracts of contaminated industrial land. Throughout, the multinational appliance giant Whirlpool dominated the town. As the company closed its last local plant in 2011, it made new plans for a taxpayer-subsidized research campus on the river, continuing its major role in plotting the transformation of Benton Harbor into an upscale resort destination.

The 530-acre Harbor Shores Golf Course is the heart of this current re-territorialization–an example of the expansion of capital in the wake of economic crisis. Harbor Shores is the product of allied corporate and nonprofit entities along with heavy public subsidization. The non-profit partners are charged with recouping investment through social and life skill improvements, philanthrocapitalist lingo for the internalization of behaviors that suit a market economy.6 For example, the initiative “First Tee” engages youth in “building character” by caddying, a kind of patronage that may be the only opportunity for some of the participating youth. Their website lists their many sponsors and accomplishments; affordable housing, drug rehab, park maintenance, and other services once the government’s purview. The site advertises the dollar value of these initiatives and tallies the people “served” regardless of how long they stay or whether services are actually provided. The commodification of affect and social dysfunction fuels today’s venture philanthropy.7

Our guide, the activist clergyman Reverend Edward Pinkney, explained that Benton Harbor’s residents (over 90% black) have been not only economically excluded, but are also vulnerable to election fraud and discrimination in the judicial system. The surrounding county is predominantly white, meaning juries, judges, and state-level officials are also often white. Some stand to profit if Benton Harbor’s future goes their way, including an heir to the Whirlpool fortune. Pinkney, who long suspected Whirlpool’s intentions on the park, now speaks for those fearing retribution from a corporate controlled police apparatus. He shows us the contaminated lots that were “given” to the townspeople in exchange for Jean Klock Park’s forest. We see a house on the 7th hole that is listed for $1.5M and before visiting working class neighborhoods where many pay more in annual rent than the houses are worth. In a city where the $5K/year annual golf course membership is half the average yearly adult income, economic apartheid is a reality.

We visit a new cafe in the arts development zone where entrepreneurs receive tax breaks to build businesses near a “river walk” that will someday connect to the boutiques of Harbor Shores. As the city changes to reflect its handlers’ gentrifying designs, housing for long time residents may well become unaffordable. In the meantime, activists try to recall the mayor.8 As the election nears, police are interrogating petition signers and Pinkney is detained. In the past year, the bodies of young black men from the town have been found floating in the river, unsolved deaths. Corporate patronage in Benton Harbor has come full circle in inflecting meaning on the word “perpetuity.”

3 . T O W A R D A T H E O R Y O F M U T U A L S E L F – R E C O G N I T I O N

Sociologist Loïc Wacquant describes the relationship between market, government and citizens as a “concrete political constellation” in which the “state redraws the boundaries and tenor of citizenship through its market-conforming policies.” This is accomplished by opening new sectors of commodification, the use of corrective workfare, zero tolerance punitive measures, and animating tropes of individual responsibility.9 It is evident this is happening Lashi and Benton Harbor–and probably in any other unfamiliar place we might happen to investigate. Specifically, both places are being marched into the tourism industry, an economic sector with global and transcontextual elements. In both cases the state facilitates the tourism and new enclosures, and a wealthy class benefits from the encroachments. But like trains running on different gauges of track, Lashi and Benton Harbor occupy different points in an arc of development, with corresponding differentials in political signification and material basis. Benton Harbor resides on the far end of deindustrialization while Lashihai society is still agrarian, in many ways informally collective, although increasingly dotted with pieces of marketized life, some willingly adopted, some resisted, and some irrelevant.

Comparisons fray when we attend to the question of political response. General similarities may be noted–for example, intimidation and a threat of violence is a problem in Lashi as it is in Benton Harbor. But responses align with differentials of historical experience, the political channels available, and what actions are accorded symbolic significance. For example, in Benton Harbor as a holdover from the centrality of voting rights won during the Civil Rights period, African American people rely on elections even though the process has been corrupted. Faithful to the Civil Rights tradition, they likewise mobilize for conventional protests when visibility seems a possibility, such as during the national spectacle of a professional golf tournament in Benton Harbor. But these kinds of demonstrations tend to be treated as pre-digested tropes, and thus become neutered expressions of simmering discontent as opposed to exercises of actual political power. As noted earlier, Lashihai villagers refused local level representation by a titular “chief.” The elimination of this bureaucratic layer was collectively organized by the women as a pragmatic solution to the problem of corruption, rather than as an act of subversion. But recusal is also consistent with Naxi people’s historical “ungovernability” in relation to imperial authority; our host rejects the “peach paradise” compensation offer by acknowledging the request and, Bartleby-like, demurring indefinitely. But to outsiders without guides and hosts, this resistance–so important to the preservation of a humane society–exists unseen, behind the opacity of a system that effaces dissent.

To remind, the fundamental problem tackled in this essay is that of finding operations of translocality and transcontextuality outside the quickness of spectacularized protest. Toward this end, we describe two places, different but similarly imperiled, that have little political recourse in the face of displacements and thuggery executed locally but driven by globalized market forces. What binds the residents of Benton Harbor and Lashihai to all those living in other places of unseen friction is their shared future horizon as non-stop entrepreneurs of the self, as human capital in the most invasive sense. But a sustained mindfulness of place, between and across contexts, will not result from an exchange of protest images or other superficial documents of discontent.

We propose mutual self-recognition as a process through which an operable political translocality might lead to the proliferation of strategic identifications between places largely invisible to the mediasphere and to each other, outside the circuits of recognition that limit exchanges to that between the subjugated and the powerful. We assemble the term from the work of Dene scholar Glen Coulthard, drawing on his critique of liberal recognition politics in the context of First Nations’ relations with the Canadian government.10 Coulthard questions the political meaning of a process in which the subaltern gains official recognition by the state and makes claims to sovereignty on that basis. He traces conventional political recognition to Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, in which the mutual dependency between master and slave renders a reciprocally intersubjective relationship, in spite of the asymmetrical balance of power. Coulthard then problematizes this dynamic through a reading of Fanon, who introduces into it the factors of psychosocialization and culture, activated in the context of colonialism.

Coulthard argues that official recognition by the state can only reproduce the essential colonial relationship, even if in an accommodated or uplifted form. He concludes optimistically but abstractly by suggesting that, following Fanon’s pathway to colonial agency, recognition be a claim made first for oneself by oneself, prior to and instead of setting oneself in relation to the external authority of the state. Thus, he argues that self-recognition moves the subaltern toward “evading the politics of recognition’s tendency to produce Indigenous subjects of empire.” We add mutual to self-recognition to denote the process of, as Coulthard quotes bell hooks, “recognizing ourselves and [then seeking to] make contact with all who would engage us in a constructive manner.”11 But, practically speaking, what is the operation of self-recognition? How do sited communities, nested within the larger and at times contradictory contexts of a culture, an environment, and a global political economy, actually go about recognizing themselves? To these questions Coulthard offers no help.

Let us suggest one possible path. When insurgent events jump borders and link contexts rapidly, visibility is a key to the dynamic. Because the register of political resistance is entirely different in places like Lashihai and Benton Harbor, ie essentially a resistance of long term noncooperation as opposed to headline-making protest, the corresponding time of visibility also must be different–both in the becoming visible and in the duration of being visible. The representations of these places, of their existence, of their subjecthood, is less about virally circulated images and time-stamped photojournalism and more about ongoing recombinations and mutations of existing cultural symbols, for the sake of self-recognition. Mutual self-recognition opens up as a potentiality when communities deploy their vocabulary of symbols, organically and immanently developed over time, to assert their dignity.

4 . R E T U R N T O T H E S Y M B O L I C

Hung Liu’s print-painting Peach Blossom Spring depicts a foursome of teenaged girls, sitting on the ground in trousers and collared coats, cross-legged, looking out at the photographer who captured this pose on an afternoon from the late decades of dynastic China. Many decades later Hung Liu paints from the historical source, setting the four figures in color, on one side of a mashed-up Chinese landscape of lakes, mountains, and the blossoms of the title. Opposite the girls is the outsized profile of an elderly woman, looking toward, or maybe literally over, the girls. The young betray the freshness of spirit that all young people possess. The somber grayness of the old generation’s representative may come from her knowledge of what follows for these soon-to-be wives, knowing that the girls’ bound feet would be but the most painfully obvious of a lifetime’s worth of unfavorable treatment. But for what might have been a late Qing-era generation sitting on the cusp of unknown revolutionary changes, the feelings of young female society must have been palpable. Mixed with the figures are a sampling of symbols from the traditional society that was then losing its authority, including butterflies, a flock of cranes, and peaches on the limb. It is the long arc of civilization, conservative by nature, pitted against urgencies stored in memory, historical contingency, and individual expectation. The girls’ feet, gathered in front of their bodies and thereby quietly revealing their common experience as a gendered class, speak to the violence of history that straddles the production of symbols. The desire for that which the peach represents, longevity and immortality, cannot be divorced from the world we really live in.

The title refers to a fable attributed to the Six Dynasties poet Tao Yuanming in which a fisherman wanders up a tributary and discovers an unknown settlement whose inhabitants live in harmony, insulated from the political strife of the fast-changing dynasties. Peach trees line the valley, a place that time forgot. After the man returns home and reports his experience, later seekers are unable to find the village, leaving its existence to the eternal imagination. Today the phantasmatic valley reads as a literary antecedent for the paradisical images advertised by Yunnan province tour operators. Hung Liu’s insertion of a gendered historical experience into the timelessness of legend counts as a political intrusion into a vaporously ahistorical plane. She re-invests symbols with meanings layered with the dignity of the female subjects, in all their specificity. Thus, the new moral of the story is that a dropout society inherits inequalities–there is no pre-social moment– even as the desire for an escape proves to be the most powerful modern marketing line of all.

We encountered this painting in July, an interregnum between the Arab Spring and Occupy, a time when the hazy fruits of revolt in some places seemed within grasp, but in Lashihai the oncoming “peach paradise” remained a suspended threat. There, in a convergence of meaning, the symbolic significance of peaches got tied to the actual fate of the farmers’ lands. The symbol will occupy time as a trophy for the winner, depending on the outcome of the impasse. And so applying Hung Liu’s artistic strategy to real life, recombining symbols in order to make visible the contradictions of people’s life experiences, is one path to self-recognition. Performing the symbolic as an intervention may even disrupt the unitary time of capital. In October, the Ohlone activist Corrina Gould addressed a crowd at Occupy Oakland. Making a mutual encounter out of an event framed as a unified protest, she quipped, “It is so wonderful to be here today with hundreds of people who want to occupy occupied land.” Indigenous people, when asked about the origins of their knowledge–which is in so many ways synonymous with their resistance–will always say ‘time immemorial,’ or farther back than anyone can remember. Gould ripped open the gap between the symbolic power of her people’s memory and a contemporary imagination of dissent shaped solely by the experience of capitalism and its unceasing power to erode a commons of symbols.

Peach Blossom Spring, Hung Liu, 104.1 x 375.9 cm, 2011. Courtesy of Alexander Ochs Galleries Berlin | Beijing, Trillium Graphics, and the artist.

N O T E S

- Neil Smith, Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space (Athens: University of Georgia, 2008), 194-199.

- Jason Adams,November 16, 2011 ”Occupy Time,”Critical Inquiry blog: In the Moment. http://critinq.wordpress.com/2011/11/16/occupy-time/.

- James and Grace Lee Boggs, Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974, 2008), 168-171.

- A debt is owed to Jay Brown for translation, and to Brian Holmes’ for his unforgettable description in June 8, 2011. “Wu Mu Cosmology: Pathways through the Modern World System,” Continental Drift. http://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2011/06/08/wu-mu-cosmology/

- “Save Jean Klock Park,”accessed April 25, 2014, http://www.savejeanklockpark.org/.

- Vicanne Adams, “The Other Road to Serfdom: Recovery by the Market and the Affect Economy in New Orleans,” Public Culture (2012) 24(1 66): 185-216. This illuminates connections between the bureaucratic apparatus and a growing philanthropic sector associated with Corporate Social Responsibility.

- “Partners in Harbor Shores Accomplishments,” Harbor Shores Lake Michigan, accessed May 1, 2014, http://www.harborshoresdevelopment.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=27.

- Phone conversation with Reverend Pinkney, Wed. April 23, 2014.

- Loïc Wacquant, “Three steps to a historical anthropology of actually existing neoliberalism,” Social Anthropology (2012) 20. 1, 71-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1489-8676.2011.00189.

- Glen Coulthard, “Subjects of Empire,” Contemporary Political Theory (2007) 6. 437-460. Thank you to Nicholas Brown for pointing us to the work of Coulthard.

- Coulthard, 439, 456.