The reporters are Matthias (nomad) and Sarah (resident (in dark blue)

At the farmer’s market. A three-piece band in the basketball gym of a school, Saturday morning. Booths suggesting the cheerful side of barely getting by. This is what neoliberalism looks like on a cold, sunny spring morning. People producing marginal objects – coffee, jam, knitted hats & shawls. The atmosphere is almost downright exuberant. Organizer of market describes how easy it was to get the space ‘donated’ by the school. Principal was into it.

Drifting through the place where you live with others lets you to see things through unfamiliar eyes. There also were places on our route that were unfamiliar to me. I didn’t want to reiterate the region’s known horror stories like the Herrin mining massacre, or the undeath of Cairo by Jim Crow, and others. Instead, I sought a more complicated picture of how people manage here. There are many gaps; it is too easy to create an overdetermining narrative, especially in a place where the population is so dispersed. I am relieved those who traveled along brought different, conflicting ways of seeing the places we visited. What if the people who are selling these marginal objects at the Farmers Market actually get a portion of their income from these minor activities? How should maple syrup be obtained? From hours of steamy labor or by enslaving plantations of trees and paying minimum wage? It is difficult to reconcile scales of expectations between the urban and the rural.

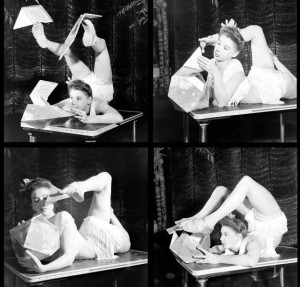

Contortionist assembling a dymaxion globe. Photo by Wallace Kirkland for Life Magazine, ca 1943

I imagined a rural industrial as encompassing an arc in scale from the hulking remnants of commodity production and appliance manufacturing, to the intimacy of farmstead crafting. It is true that neither of these poles seems sustainable. Perhaps the uncertainties of how global fiscal maneuvering will next intervene in the lives of people here produces a sense of permanent transition, permanent distrust and uncertainty. Curiously, one of the leading 20th century theorists of appropriate scale, designer Buckminster Fuller, made Carbondale his home for 11 years. Perhaps “Contortionist assembling Dymaxion,” from Life Magazine circa 1943 best characterizes the rural industrial landscape; equal parts bravado, creativity, flexibility and pathos. And a little perverse.

The Bucky Fuller House. Fuller taught in the College of Art and Design at Southern between 1959 and 1970. His lectures were legendary for their duration and many students were attracted to the school to because of him. The home-dome is in a tree-filled residential neighborhood mostly built in the first half of the last century. Fuller’s dome has a bigger footprint on its corner lot, and a decorative concrete water garden? fountain? kiddie pool? It is unclear what the intentions were exactly.

The house, a geodesic dome, inside a geodesic dome of scaffolding, to protect it as money is raised for renovation. Our guide describes Fuller as “one of the DaVinci’s of the last century,” noting how ironic it is that there’s so little about Bucky around town. The absence of obvious tributes to his genius chalked up to “politics,” more specifically “old wounds” & the sense that Fuller was “a rogue” without the “proper degrees.” General consensus is that he was a FREE THINKER & pretty damn good at it. His domes are scattered across the region.

This dome, “a labor of love” which Fuller & his wife lived in for several years, has been approved for preservation by the National Park Service (division of the Department of Interior) but funds must be raised privately for its restoration. $87,000 raised toward a Save America’s Treasures matching grant—another $38,000 needed. (Contribute on-line @ www.fullerdomehome.org.)

This dome was built in 1969 from a kit sold by the Pease (?) company; it required only one day to assemble once the foundations were poured. The exterior, within the gloomy light of its blue plastic/nylon protective curtain, is heavily draped in layers of asphalt shingles that reproduce the geodesic pattern, multiply it, yet also burden it, dragging its futurity toward earthen realities. Reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright houses in that there are obvious problems with roof leakage; as our guide explains, Fuller, like Wright, was a visionary whose architectural designs surpassed the technical/material know-how of his time; he was “ahead of the technological curve.” These days, advances in joining and sealants (developed to solve problems with skylights) would allow even relatively affordable domes such as this one to be much more waterproof. Our attention called to the base for “missing godawful light bulbs,” of Fuller’s design, but which were said to resemble “a WW II helmet for a garden gnome.” Nonetheless they will be replaced as part of the restoration. Also original plantings and a fence across the front, which Fuller erected for the sake of privacy.

Inside, the dome’s bubble is bisected into delightfully different-sized spaces. A large open area on one half, with windows and a loft. The other half, underneath the loft, is a warren of tiny passages, closets, a humble kitchen & bath, small bedroom. We learn about dome frequencies. There are only two forms in the geodesic dome, both based on the triangle, “where nature gets its strength.” This is a “three-frequency” dome; a ‘perfect’ geodesic is a sphere. Most domes are based on a 20-sided cube. Bucky DISCOVERED, not invented, the dome; it has always existed in nature.

Time passes differently inside the dome; we are enclosed in unusual space, and feel differently than we would in our usual squared houses. Upon reflection this is what makes Fuller so important. He proposed in theory & practice the possibility of taking housing away from the SQUARES. Around the age of 30, suicidally depressed, he decided to live life w/out taking any knowledge for granted. He began to make notes based on his observations of the world every fifteen minutes and experimented with sleep patterns. His goal was not a political revolution, but a revolution in design. He believed that industrial modernism meant that no one need by homeless; he proposed social justice infrastructure, borrowing the aesthetics of futurism. Having spent time in the Navy (WW II), a developed housing designs based on military building technologies. He developed games for middle-schoolers and wrote popular books, such as Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1968), arguing the management of finite resources was the most important task for future generations. He was a populist—later partnering with the Walt Disney Company to develop a Spaceship Earth attraction at Epcot Center. He did not accept the notion of original invention, preferring to think of his concepts in terms of synergy; he used other people’s theoretical and design languages to produce metasystems, efficiencies.

Crab Orchard. We drive into the parking lot of a community college near the far western branch of Crab Orchard lake. College’s signal their status with a bell tower and a pond, and this one has both. But what’s in that pond? You would not want to go wading in that water!

We pull into the outermost ring of roads and buildings surrounding the Crab Orchard munitions plant; ghostly white and “flesh-colored” windowless boxes and corrugated metal Quonset huts, apparently empty. Much goes on underground. No signs to indicate what is or was here. Back in there somewhere, behind chain-link fences and unmarked roads, are the former (current?) buildings used by General Dynamics for the production and storing of munitions. Navigation systems for missiles, drone guidance systems, working with the Israeli defense but this is not a particularly hightech industry. A whole secret life back in there; something going on; we haven’t been told the whole story. But we know it by its CONTAMINATION! Deformed animals! Mercury! PCBs! Lead! Depleted uranium! General YUCKINESS! You do not want to eat the fish in this lake!

Our guide tells us a story: “When I was a young man I worked at a canoe factory that rented bunkers here; some of the bunkers still had munitions in them. Somebody was smoking near one of them and blew up a keg of gunpowder & was badly burned.”

FOLLOW THE URANIUM TRAIL

Herrin, Illinois. We met our local guides in an Italian restaurant; stood in a long line for deli sandwiches—a popular lunchtime hangout. Then began our walk in the abandoned lot next to train tracks. A several-blocks long building that used to house vendors’ stalls, buying and selling produce shipped in & out on the trains, “empty for ages” now. We follow the tracks to two abandoned factories, picking up an amazing amount of local history related to personal, communal & economic life of the town. Who lived where & why. The brick buildings owned by wealthy families; the poor supported by mutual-aid societies organized by Italian immigrants. Once the town’s economy was in the earth—coal mines so close the workers walked to and from them in morning & evening dark. In its heyday in the 1940s and 1950s, Herrin was a commercial center—clothing companies producing the latest prairie fashions. One of our informants said he he read all the obituaries and that every woman who died in her 80s or 90s had worked in the clothing factory. On Saturdays, visitors came from the whole southern half of Illinois for the latest fashions and an amusement park.

I asked several of our guides how they’d come to have so much knowledge of the town; one said he “just liked to pay attention,” the other that “if you don’t know your history, you’re liable to repeat it.” He explained that his parents had grown up in the Great Depression & taught him to care for the few possessions he had—one of these, presumably, being town history.

I asked several of our guides how they’d come to have so much knowledge of the town; one said he “just liked to pay attention,” the other that “if you don’t know your history, you’re liable to repeat it.” He explained that his parents had grown up in the Great Depression & taught him to care for the few possessions he had—one of these, presumably, being town history.

The town’s third-wave of industry was post-war manufacturing of durable goods—an enormous Whirlpool factory, now shuttered. We stand outside it and wonder: what will be next? The health-care industry is current the largest & fastest growing employment sectors. Our informants are interested in industrial agriculture—a fish farm in the old Whirlpool plant. Just outside of town we will pass the latest industry: NATURAL ENRICHMENT INDUSTRIES, which makes TCP or Tricalcium phosphates: used in binders for pills & “food conditioners”–to prevent clots in cake mixtures and other ready-made cooking ingredients. The manufacturing of smoothness. Producing the deep structures of daily homogeneity. The policing of ordinary consistency. What are all the anti-clumping agents in our society? And phosphates are in limited supply—there are only so many in the earth…

But first, outside THE ABANDONED STAPLE FACTORY we hear about the various chemical processes that once went on inside: acid baths; the stream alongside used to bubble & almost glowed. Inside, we wander enormous gloomy spaces, tour demolished offices and wrecked machines once used for grinding down the points on staples, a very few of which we discover in the dirt outside. Spray-painted on the interior wall in a very careful, rational font, are several sentences, spaced between the girders:

Don’t fuck your mom, that’s gross.

Quit smoking pot. You’re stupid enough already.

Meth, thank you for thinning out the retards.

You’re the sperm that shoulda been flushed!

How to interpret this message? It appears to be directed toward delinquents/perverts/drug users who would make use of this space for recreational purposes. The first sentence as a statement of the general law: the foundational taboo. Then two passages laying down the rules and assigning roles: stupid people smoke pot, which makes them more stupid. Retards smoke meth, which thins out the retard population. There is a prohibition on pot but praise for meth. The final sentences closes the sequence with a nihilistic flourish—existence condemned more generally & in the vernacular.

On the way out of Herrin, a local store with a sign in front suggestive of the intensity of the region’s economic depression:

WE STOCK MILK & BREAD

And less visibly, the places we did not drift through such as the town of Colp, only a few minutes to the west, just a detour off our route, outside the frame but present, an all black town that is a living artifact of a Jim Crow and segregation. Cathy drops off the People’s Tribune there as part of her delivery route. During the heyday of Herrin and supposedly through the 50’s, one of Colp’s clubs hosted all important jazz acts and there is definitely more to learn there about the relations and exchanges between whites and black then and now.

Scratch. A brand-new brew pub. After two years in development, it opened one month ago. It concentrates on the micro & the local. Two healthy-looking young people a few years out of college who took over two acres of an 88-acre farm owned by one of their parents. Their goal being to “bring to beer the ethic of localism many people want in their food.” They brew only 10 batches at a time—just enough for two-weeks worth of beer (and they are only open on the weekends) & constantly change their recipes. Their licorice basil stout and roseroot, for example, use local plants in order to produce a LOCAL FLAVOR.

They grow their own hops right outside—growing hops is easy, can be done almost anywhere. Barley is more difficult. Once upon a time breweries used barley grown locally—small batches threshed by people who were used to threshing; but now most of them buy malt from CARGILL. Today small batch malting is a challenge.

I am struck by the medievalism of the whole operation. Behind the bar inside the small, wood-beamed & benched pub is an enormous, exquisitely detailed watercolor painted onto the plaster of a chimera. Outside, wood walkways lead through the mud churned up by recent construction & they are building kilns (for making pizzas to be sold w/ the beer) out of wattle. Everything local, micro, and built by hand as much as possible. Is it only a veneer, a new kind of brand? After all, the modern highways bring people to the place & the brewing tanks are stainless steel… Or something more than that—the articulation of a desire that marks a more stable, concretized libertarianism? An ethos commensurate with the refusal to get along by going along? Will this brew pub be here twenty or a hundred years from now? Will people hover by in their helio-copters or hove up in horse-drawn carts?