Everyone knows the North Branch of the Chicago River no longer flows into Lake Michigan. Instead it has been rerouted into the South Branch, itself transformed into the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. This tremendous engineering feat – a precursor to the Panama Canal – serves not only to keep the city’s drinking water clean, but also provides the crucial final link of a waterway from the Mississippi River to the Great Lakes. Barges ferry some 16 million tons of cargo a year up and down the canal, mostly coal, oil, steel and bulk construction materials.

Everyone knows the North Branch of the Chicago River no longer flows into Lake Michigan. Instead it has been rerouted into the South Branch, itself transformed into the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. This tremendous engineering feat – a precursor to the Panama Canal – serves not only to keep the city’s drinking water clean, but also provides the crucial final link of a waterway from the Mississippi River to the Great Lakes. Barges ferry some 16 million tons of cargo a year up and down the canal, mostly coal, oil, steel and bulk construction materials.

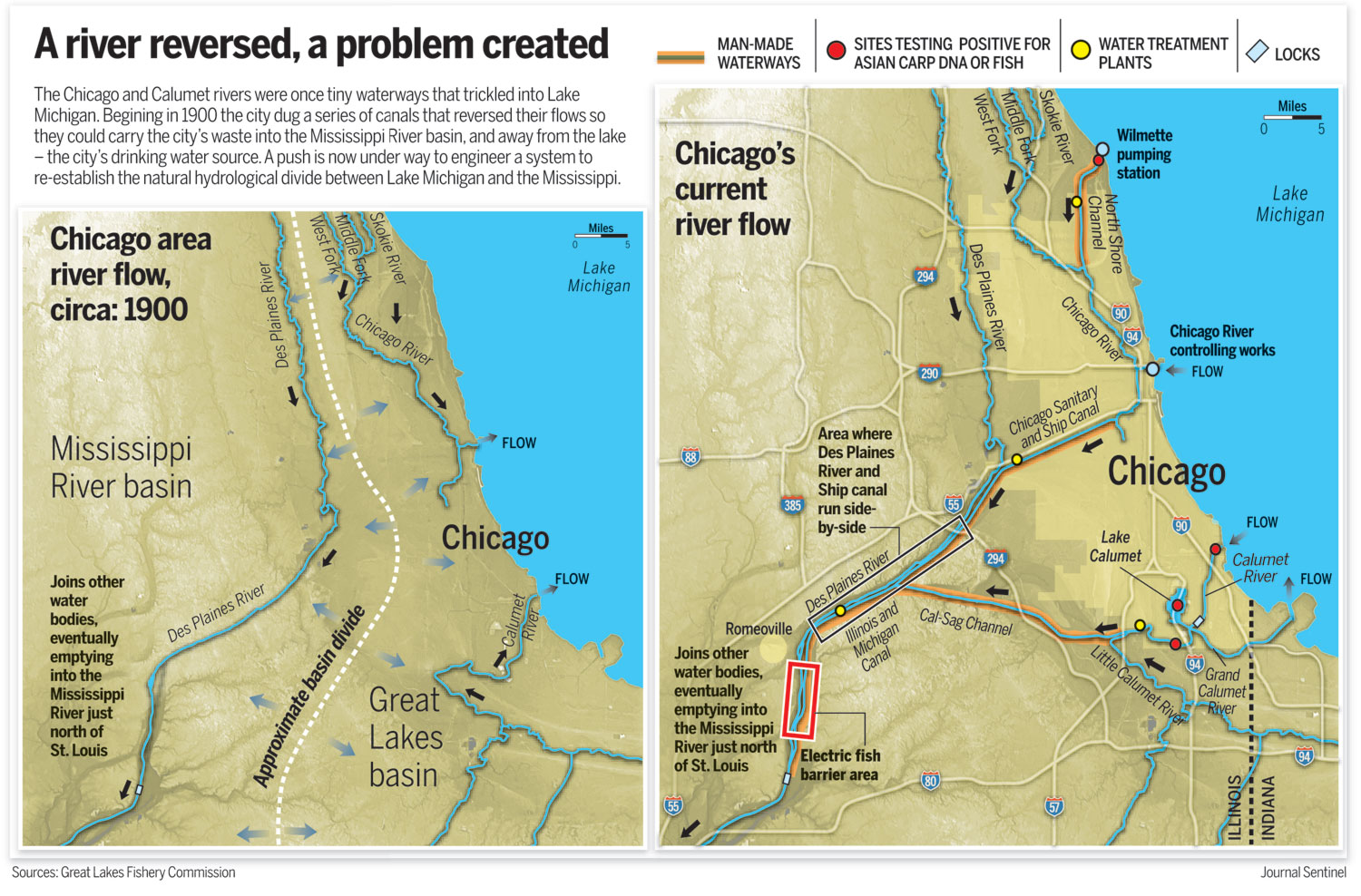

The design podcast “99% Invisible” has a Reversal of Fortune segment that recounts the three-step process that changed the region’s hydrology. First, beginning in 1857 and continuing for about twenty years, Chicago’s sewage system was installed over roads, buildings and entire neighborhoods jacked up ten feet above their original level. Then, in 1865 when it was understood that the new sewers were going to foul the city’s drinking sources, a tunnel was dug two miles out into the lake in order to get fresher water. Finally, from 1892 to 1900, the sanitary canal was dug at a depth of some 25 feet in order to literally flush the city’s sewage over the continental divide, down the Illinois River, into the Mississippi and finally, into the Gulf of Mexico.

From 1911 to 1922, the Cal-Sag Canal was additionally dug to connect the Little Calumet River to the Sanitary Canal. The outlets of the Chicago and Calumet rivers were outfitted with barriers and locks to keep the sewage out of Lake Michigan. With this third phase, the outbreaks of cholera and typhoid that had plagued the city were finally over. The picture above shows what might be the last piece in this elaborate engineering system: the just-completed barrier and pumping station at the end of the North Shore Channel, which is primarily used to pump lake water into the channel, so as to force its stagnant flow onward to the Chicago River and ultimately to the Mississippi.

Everyone celebrates this achievement, and feigns a bit of horror when torrential rains force the city to re-reverse the flows, sending untreated sewage directly into the lake. But how many have can even begin to imagine the ecological consequences of breaching a continental divide?

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

In a brilliant series of articles on the Great Lakes for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, reporter Dan Egan explains the history of the Sanitary Canal, its ecological consequences and some proposed solutions. Here is a long quote from his piece “Deep Trouble”:

Because the five Great Lakes are actually one giant, slow-motion river flowing east to the St. Lawrence, Chicago River water that historically flowed into Lake Michigan ultimately tumbled over Niagara Falls, down the wild, massive St. Lawrence River and out to the North Atlantic.

Water on the other side of that marsh trickled into a river that fed the Gulf of Mexico-bound Mississippi River. In big rains, the marsh occasionally, temporarily, turned into a sloshing swamp where water could drift in either direction.

Chicago destroyed the natural separation between the basins in the mid-1800s with a relatively crude navigation channel that opened a pathway for goods and people to float between the Great Lakes and Gulf of Mexico. That leak in the continental divide turned into a torrent in 1900 with the opening of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, a man-made waterway between the two basins wide enough (160 feet) and deep enough (about 25 feet) to actually pull the Chicago River – and all its waste – backward.

The river reversed direction because the 30-mile-long canal that linked with the Mississippi-bound Des Plaines River was at a lower elevation than Lake Michigan. So the water had no choice but to oblige gravity, reverse its course and head for New Orleans.

Chicago leaders felt they had no choice but to undertake what amounted to a replumbing of the continent. The city’s namesake river doubled as its sewer and as long as it flowed toward its drinking water intakes in Lake Michigan, people were bound to suffer. As many as 2,000 Chicagoans in the 1890s were dying each year from typhoid fever.

The canal project was considered an environmental success in an era before the lakes were open to global shipping, when nobody pondered the biological costs of bridging the two massive basins. But now the threat posed by dozens of unwanted crustaceans, protozoa, algae, plants, mollusks and fish spilling through the breached divide has become clear as a zebra mussel-infested lake.

Today the canal is recognized by many as one of twin blunders that destroyed the ecological isolation of the Great Lakes. The other was construction of a shipping channel between the Great Lakes and Atlantic Ocean.

The St. Lawrence Seaway, which was completed in 1959, tamed obstacles such as Niagara Falls and the roaring St. Lawrence River with a system of canals, channels and locks to allow deep-draft ocean vessels – and all the biological pollution clinging to their hulls and lurking in their ballast tanks – to sail into the lakes from ports around the globe.

The Great Lakes are now home to 186 non-native species, some of which have ravaged native fish populations, spawned noxious algae growth and triggered botulism outbreaks that have killed tens of thousand of birds. Federal regulators this year ordered a multiyear phase-in of ballast water treatment systems on Great Lakes-bound freighters to block new seaway invasions, though many are dubious the regulations are stiff enough to solve the problem.

This would be mostly just a Great Lakes dilemma were it not for the back door from the lakes that Chicagoans opened to the middle of the continent.

Pressed by the Asian carp threat to examine the extent of ecological danger posed by the canal, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers last year identified dozens of “high risk” organisms poised to ride its waters into or out of the Great Lakes. Most are species few have ever heard of. The tubificid worm. The testate amoeba. The bloody red shrimp…

Last year 17 attorneys general from South Dakota to Missouri to Arkansas wrote congressional leaders demanding “immediate federal action” to “completely sever the ecological connection between the basins.”

“All our states, which are in or connected to these basins, face severe harm as non-native aquatic species, such as zebra and quagga mussels, invade our waters, disrupting ecosystems and damaging our economies,” they wrote. “We all face the threat that more invasive species will move, in both directions, between the basins through the key artificial pathway that connects them” – the Chicago canal system.

***

Dan Egan – along with many others – advocates a $4 billion plan to re-reverse the flow of Chicago’s river systems, both to stop the movement of invasive species into the Great Lakes and to end the city’s pollution of downstream waters. This would entail not just building new dams, locks, and perhaps an overland cargo-transfer system to halt any flow whatsoever across the continental divide, but above all it would entail redoing Chicago’s water treatment infrastructure, separating the storm drains from the sewage and actually sterilizing the purified water at the end of the process, instead of releasing live intestinal bacteria as is currently done. You thought Bubbly Creek was a thing of the past? There is still a lot of work to be dome on Chicago’s sanitation infrastructure.