“We are so fortunate to be living now because the challenges are so many and we need to use our imaginations in new ways.” Grace Lee Boggs

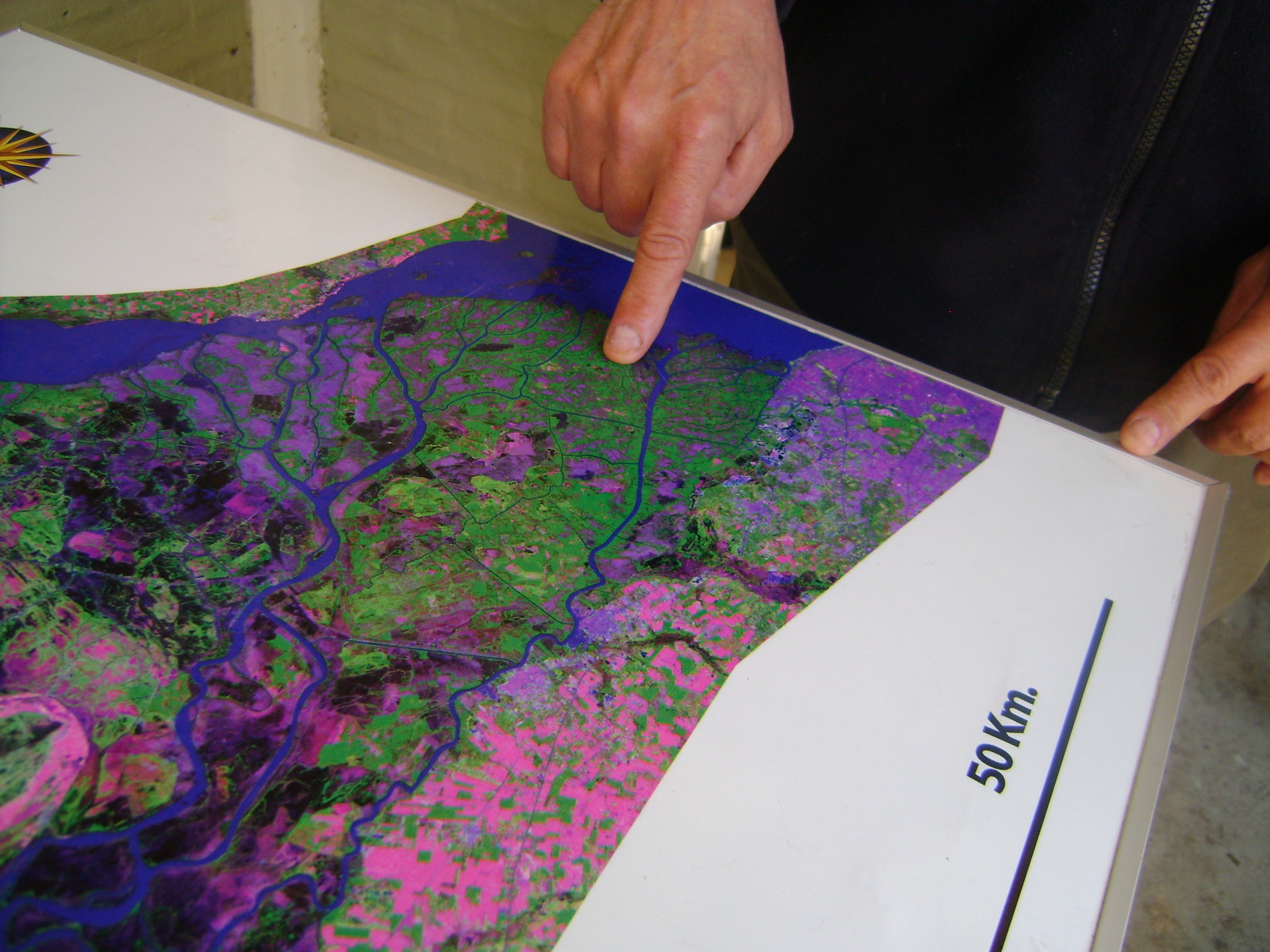

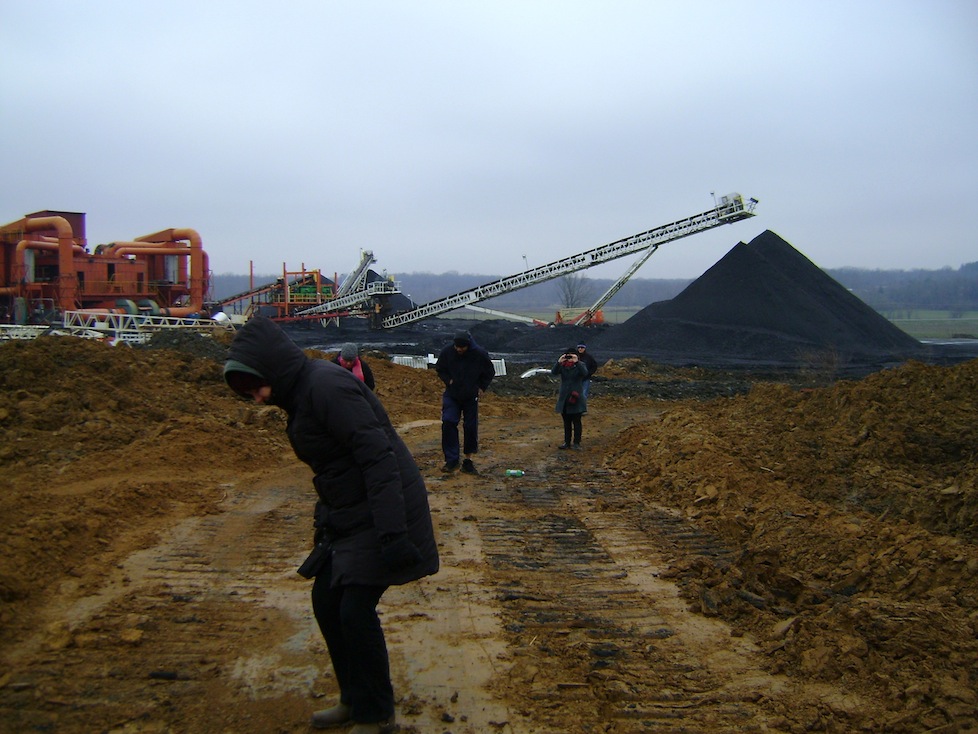

In June this year, torrential rains at Iguazú led to the closing of tourist sites, and the platform for viewing the waterfalls was all but destroyed. The upper Paraná was said to be carrying 33 times its usual flow and near Ascuncion, and farther west again in Paraguay, at least 300,000 people were flooded out of their homes. This was a month before we flew from Chicago to Buenos Aires, and when our group arrived at Rosario in late July, the still expanding floodwaters were speeding flotsam and freshwater weeds along its swollen surface. Rosario is quite distant from where the Rio Pilcomayo flows into the Paraguay and then joins the Paraná, but people in that city know it takes 25 days for upriver floods to bring the river up along their own shores. The flooding becomes more frequent as land upstream is deforested, mined and paved for roads and cities. Do the people know this too? And I wonder whether the people in St. Louis, near where I live by the Mississippi, know how many days it takes for upstream floodwaters to reach their banks. Those intervals between floods here and floods there might open a window in the skew of time between this place and that, north and south, that illuminates the interdependencies of our fortunes. This meeting is then a question of how to interrogate our temporal and causal connections to locate the time of a river. And to learn how the patterns that emerge from a river and its basin might address the daunting problem of how restorative ecological engagement is so outscaled by global financial ambitions. As Graciela Carnevale points out, there is no more need for growth. How then can humans move toward reinhabiting the basins and rivers as partners, rather than as exploiters?